Plant Hormone

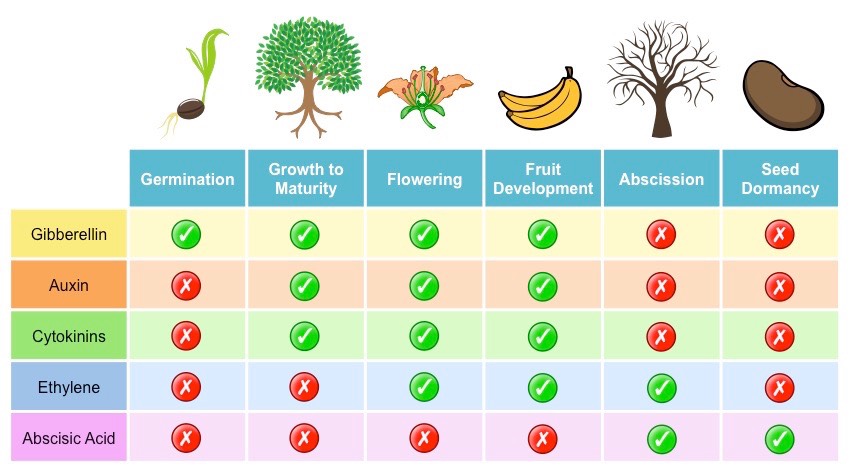

Plant hormones, also known as phytohormones or plant growth regulators, are chemical substances produced by plants that regulate various physiological processes. These hormones play a crucial role in controlling plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stimuli. There are several types of plant hormones, each with its specific functions:

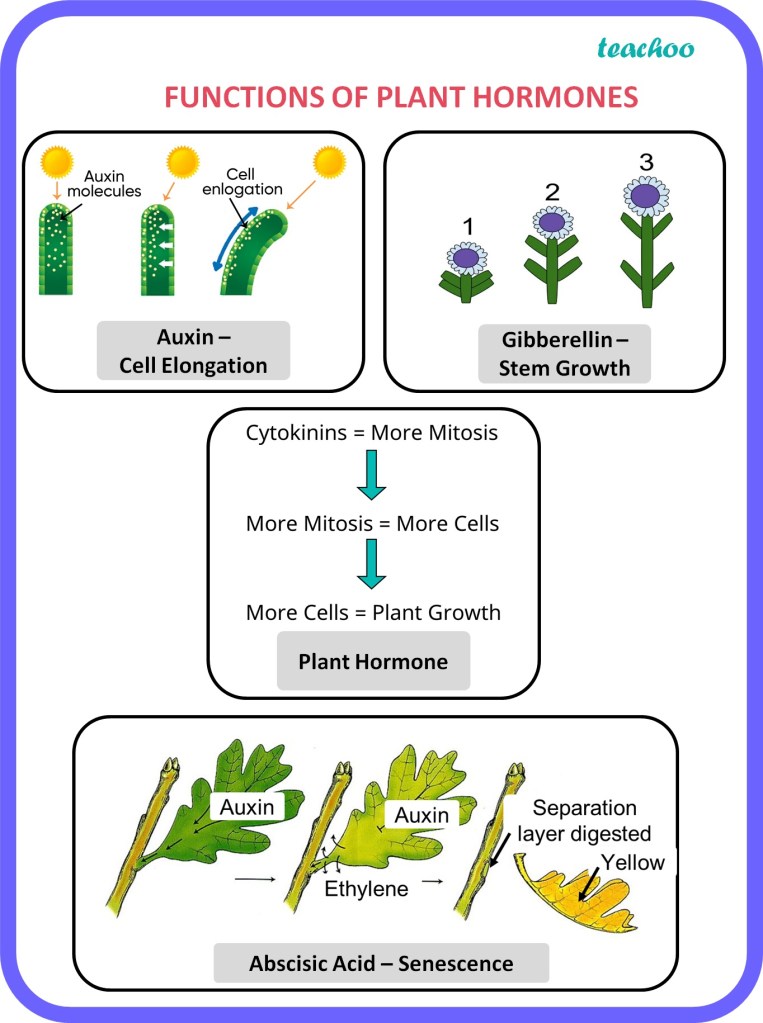

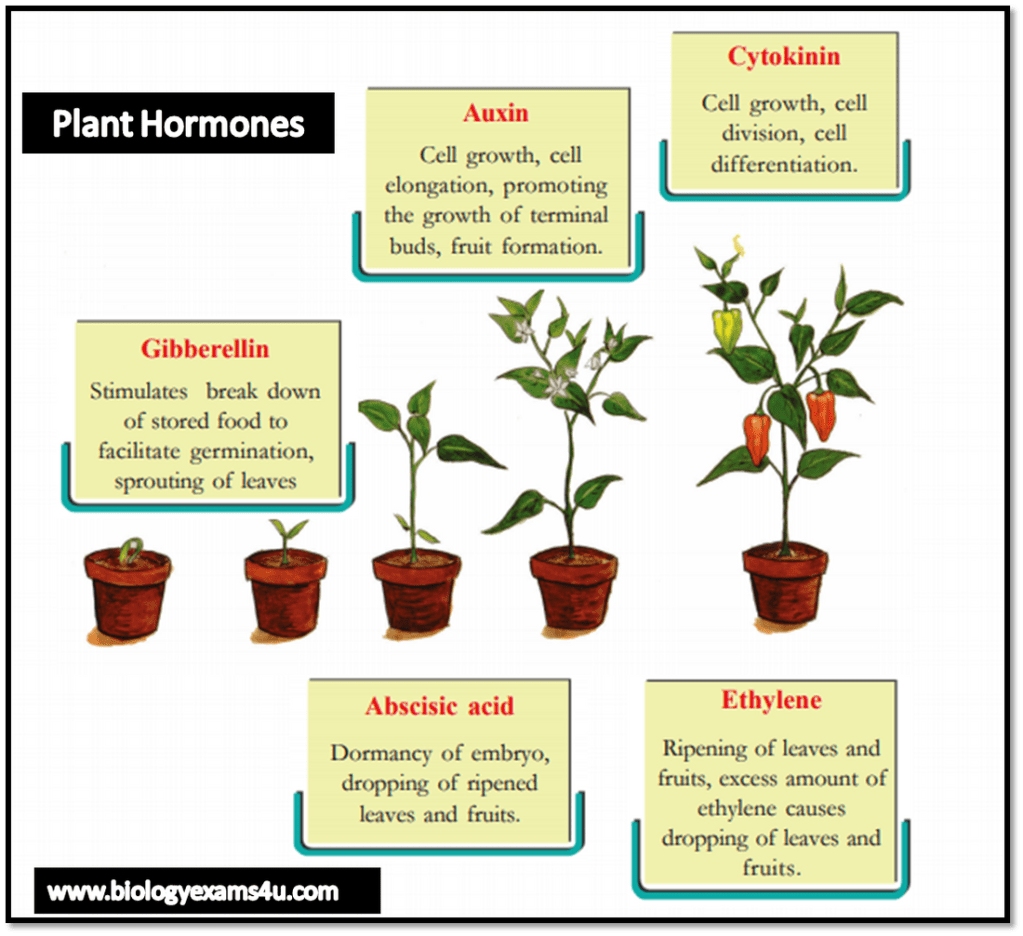

- Auxins: Auxins are primarily responsible for regulating cell elongation, apical dominance, and root initiation. They control tropisms, such as phototropism (bending towards light) and gravitropism (response to gravity).

- Gibberellins: Gibberellins promote stem elongation, seed germination, and flowering. They also play a role in fruit development and breaking seed dormancy.

- Cytokinins: Cytokinins stimulate cell division and promote shoot formation. They also influence root development, delay leaf senescence, and regulate nutrient transport.

- Abscisic Acid (ABA): ABA is involved in stress responses, such as drought tolerance and seed dormancy. It regulates stomatal closure, preventing water loss from leaves.

- Ethylene: Ethylene is a gaseous hormone that regulates fruit ripening, senescence (aging), and abscission (leaf or fruit drop). It also influences plant responses to stress, such as pathogen attacks or mechanical damage.

- Brassinosteroids: Brassinosteroids promote cell elongation, cell division, and differentiation. They are involved in regulating plant growth and development, particularly in stems and pollen.

- Jasmonates: Jasmonates are involved in various processes, including plant defense against pathogens and herbivores, regulation of fertility, and responses to environmental cues.

These hormones often interact with each other and with external stimuli to coordinate plant growth and development. They can act locally or be transported to different parts of the plant to elicit specific responses. Understanding the functions and interactions of plant hormones is essential for plant biologists and agronomists to manipulate plant growth, improve crop yields, and develop stress-tolerant varieties.